So far, the Scarcity Zero framework enables production of three out of five critical resources: electricity, water and fuel. But while electricity and fuel can be transported relatively easily, water is a different story. We might be able to leverage Multi-Stage Flash Distillation technology to produce a lot of water at the coasts, but how do we get it inland?

Scarcity Zero’s proposed answer to that question is the National Aqueduct, a system that arguably functions as the heart of the framework. In concept, it’s a nationwide array of modular, above-ground pipelines and storage facilities intended to transport billions of gallons of water to any location in the country. In function, it serves four critical roles:

- Completely solve drought and water scarcity anywhere the network serves.

- Operate as a fourth energy source alongside renewable-integrated cities, LFTRs and CHP Plants.

- Serve as a gigantic nationwide battery for renewable energy.

- Provide endless, sustainable irrigation for agriculture and synthetic material production.

Thanks to three things we’ve been perfecting for the past 50 years: oil pipelines, high-voltage power lines and interstate highway networks, not only do we have the free space and wherewithal to build this system, we’ve already built it for other substances – at higher stakes and with higher difficulties. To elaborate, consider a series of three images. First, if you recall from Chapter Two, we see that our nation has a highway system connecting nearly every area of our country:

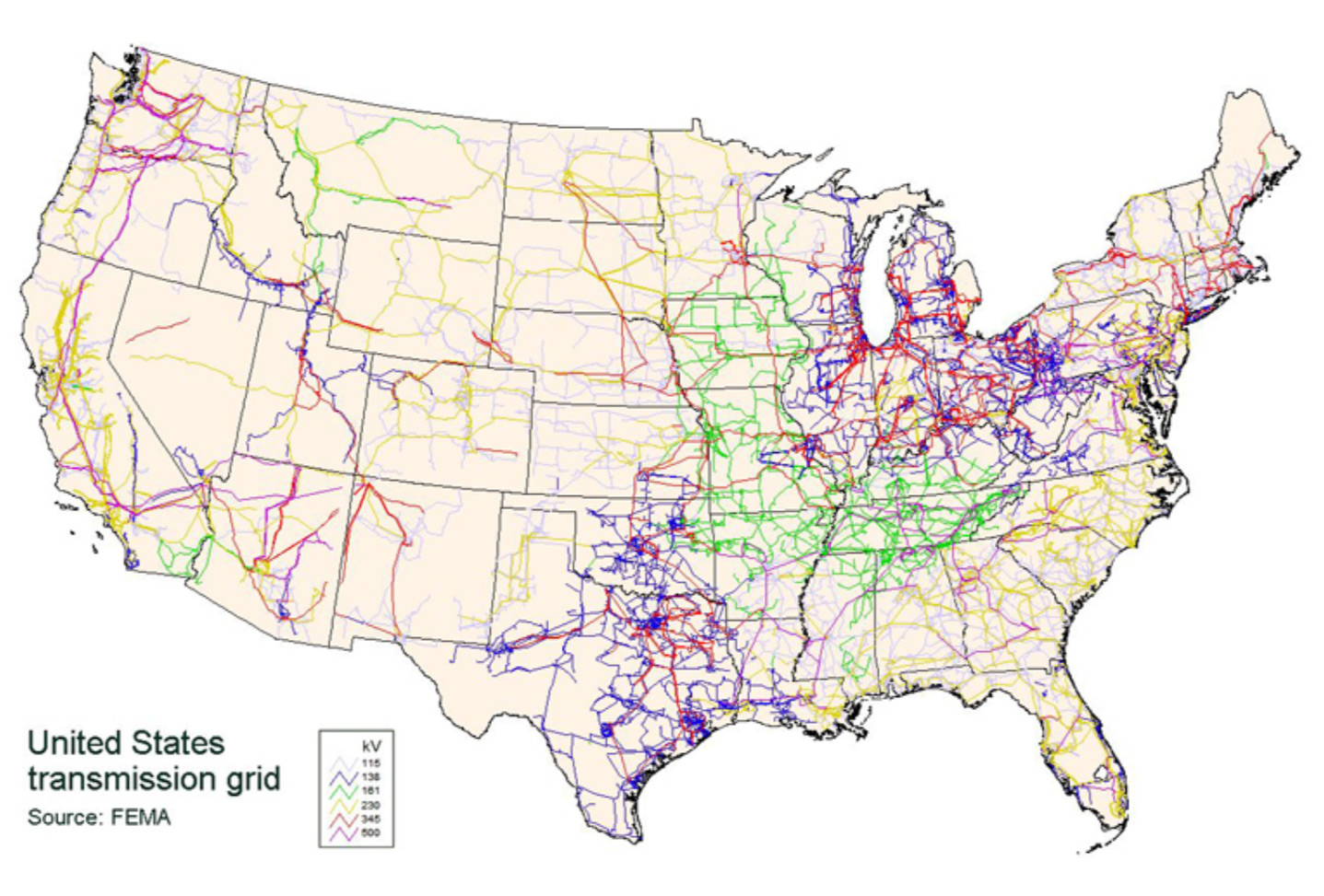

Second, consider a map of nationwide power transmission lines:

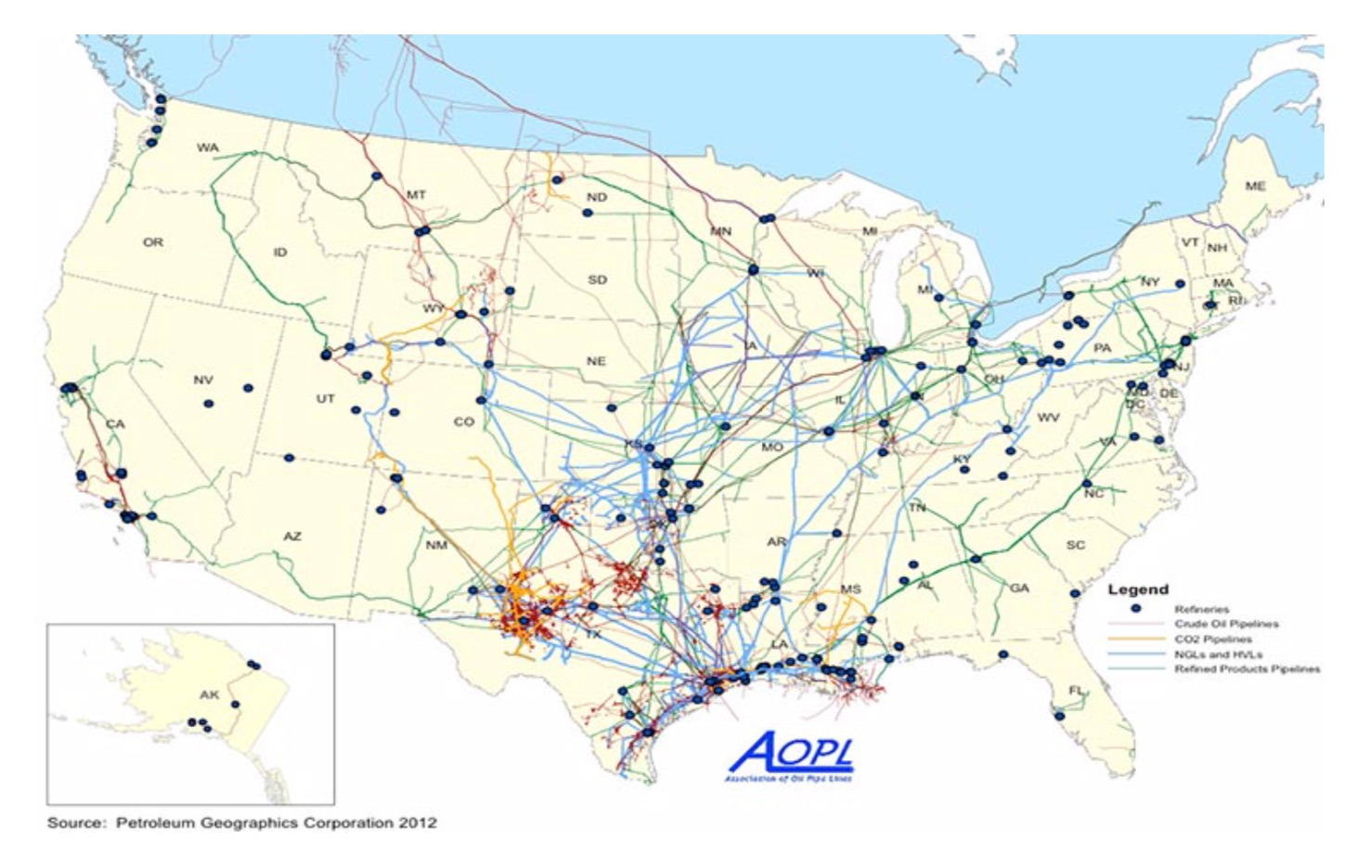

Third, consider a map of nationwide fossil fuel pipelines and refinery networks:

From these maps, we can derive two important conclusions:

- Highways and high voltage power lines give us plenty of free space to run water pipelines. Our road networks provide ample open space to install solar panels while removing the requirement to buy land, as this land is generally owned by public services that have exclusive authority to build on them.

Roads and highways also have clearance at each side and tend to be flat and straight – a trait usually shared by high voltage power line networks. This gives us thousands of miles of open, unused space to build a National Aqueduct. As this space has been cleared of potential obstructions beforehand, construction in these locations has far fewer obstacles than commercial land parcels.

Additionally, their close proximity to power systems (either integrated renewables, LFTRs or CHP Plants) gives the National Aqueduct plenty of energy to power sensors, pump stations, purification mechanisms and heating elements to help keep water hot. This hot water functionally acts as a “battery” – further discussed in the next chapter – and the potential energy stored within it can be harnessed alongside pipeline-mounted solar panels and turbines to generate immense electricity.

- Running water pipelines is feasible. We know that the National Aqueduct will work as described because we’ve already built a similar network of pipelines for fossil fuels today. Our nation has thousands of miles of oil pipelines that already work in the same way as water pipelines would in this context, and oil pipes are necessarily built to a higher environmental standard than we would need with water.

Water pipelines can come factory prefabricated and be designed for rapid, modular construction. Environmental risks are reduced, as the only substance a leaking water pipeline would spill is fresh water. In tandem, modular deployment and lower environmental risk would allow us to build a water pipeline network at a lower overall cost than with oil pipelines. We can also use the lessons we’ve learned with oil pipelines to get a head start, as the expertise needed to plan and build such a pipeline network already exists.

Much of the work involved with developing a National Aqueduct has already been done for us in terms of research and development, engineering, and methods of implementation. But to have the National Aqueduct accomplish its intended goals and meet our needs in full, we’ll need to establish a few requirements for the system:

Efficiency, reliability and affordability: Humanity has a fresh water requirement of trillions of gallons a year. While Scarcity Zero is capable of producing that much water in abstract, delivering it with any effectiveness must be efficient and inexpensive. A water delivery system must also be reliable, as any given industry or city can’t depend on an external water source if its reliability is questionable.

Scale of delivery: Whatever system we use to transport fresh water must work over thousands of miles, as water must be delivered from the coasts to areas deep inland. And as the land we have to work with isn’t flat with consistently warm weather, this system must also be deployable over varied terrain and climates – especially cold climates.

Control of operation: A water delivery system must be locally controlled, as a centralized control structure would be incapable of efficiently managing the water requirements of every agricultural and population center throughout the country. There must also be redundancy in the system – for example, allowing a city in the central United States to receive water from multiple routes in case one becomes incapacitated by some unforeseen event, such as a tornado or earthquake. This calls for a “smart” system approach that would have the ability to both monitor and manage how water is distributed from the point of desalination to the final point of consumption – both locally, regionally and nationwide.

Modular construction and ease of maintenance: Modularity is essential to ideal system design, providing benefits and cost savings in terms of construction time, standardization, reliability and maintenance. Any system to transport water would have to meet these standards by allowing its components to be installed and/or replaced rapidly by design.

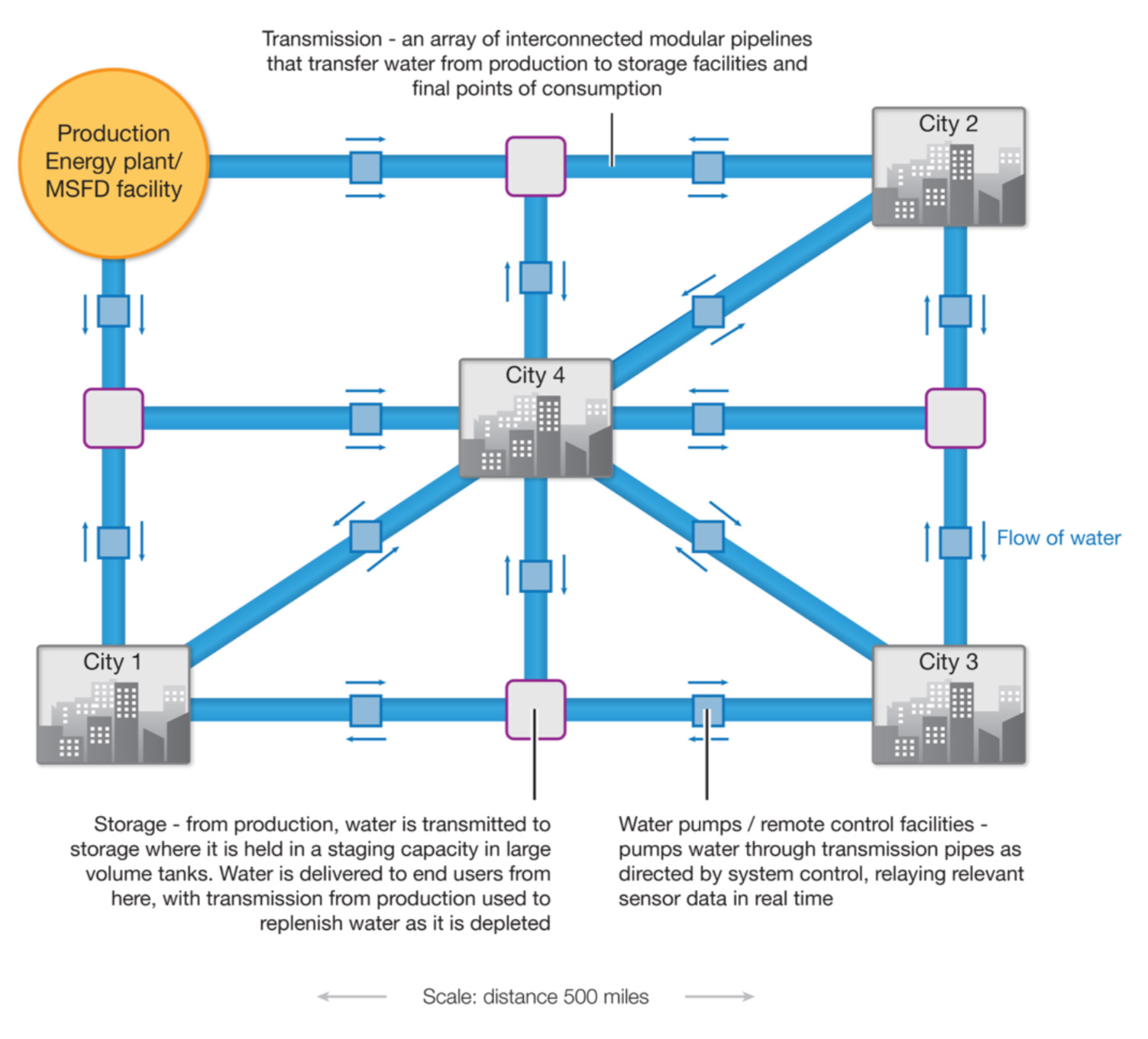

To meet all of these requirements, the National Aqueduct would be made of a “smart grid” of above-ground pipelines, storage tanks, and pump stations that would transport desalinated fresh water from the coast to any area inland. These pipelines would feature interior turbines and exterior solar panels that would generate electricity, a portion of which would then be used to keep the water supply hot to thermoelectrically generate power at night. If built, the National Aqueduct would enable us to provide for our national fresh water needs without having to rely on local water sources ever again.

That statement is worth repeating: The National Aqueduct, in conjunction with CHP Plants, would allow us to have unlimited fresh water. And that water would never need to come from the ground, a lake, or a river, unless we wanted it to. This would give natural water sources time to replenish, decreasing much if not all of the drought impact we’ve been experiencing as of late and benefiting the environment as a whole.

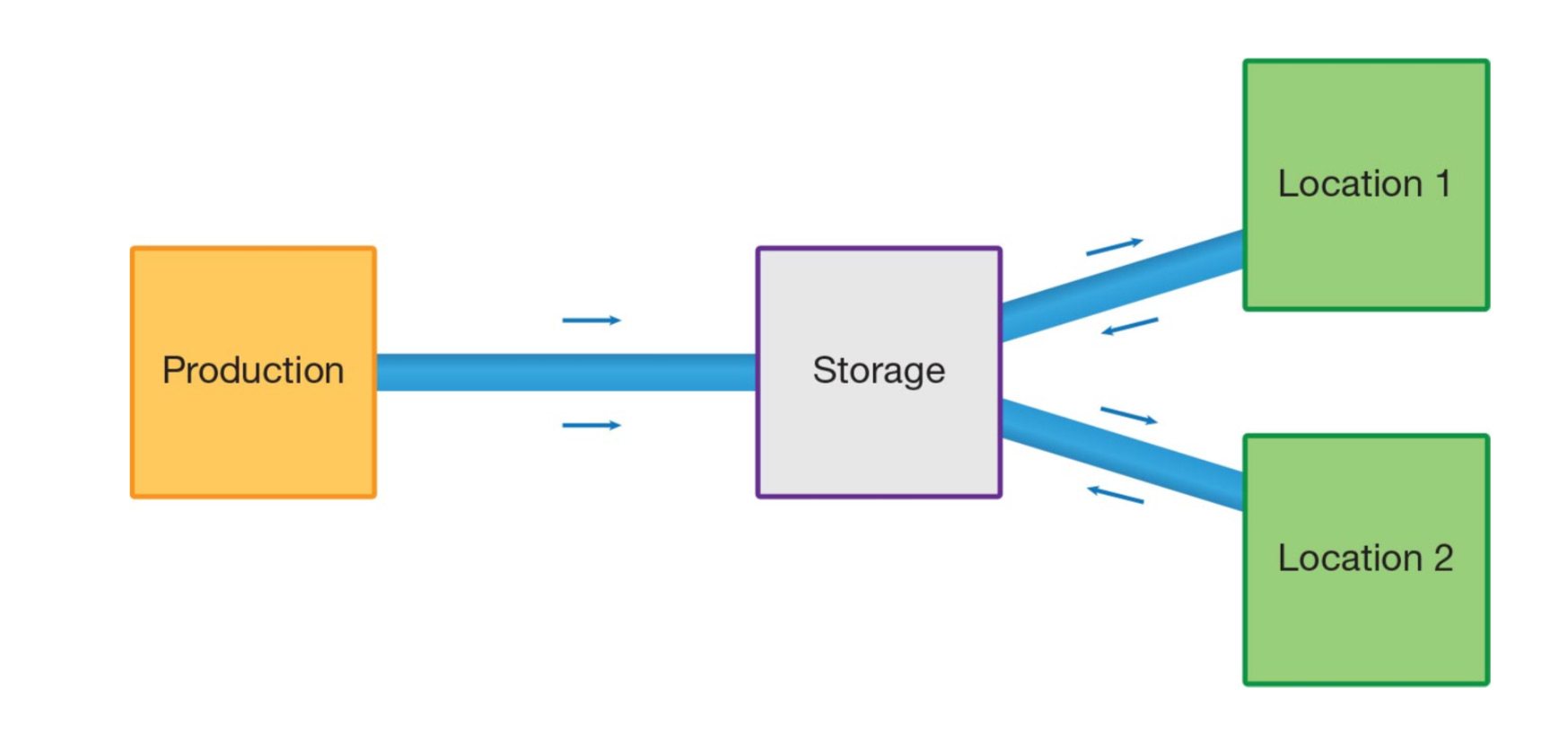

The National Aqueduct’s system consists of four primary components: production, transmission, storage and control:

Production

Production is comprised of Multi-Stage Flash Distillation (MSDF) facilities, ideally as part of CHP Plants, as described last chapter. To summarize, these facilities would use the waste energy from LFTRs to power saltwater desalination on our coasts, which apart from the water devoted to producing hydrogen would effectively give us an endless supply of fresh water.

Transmission

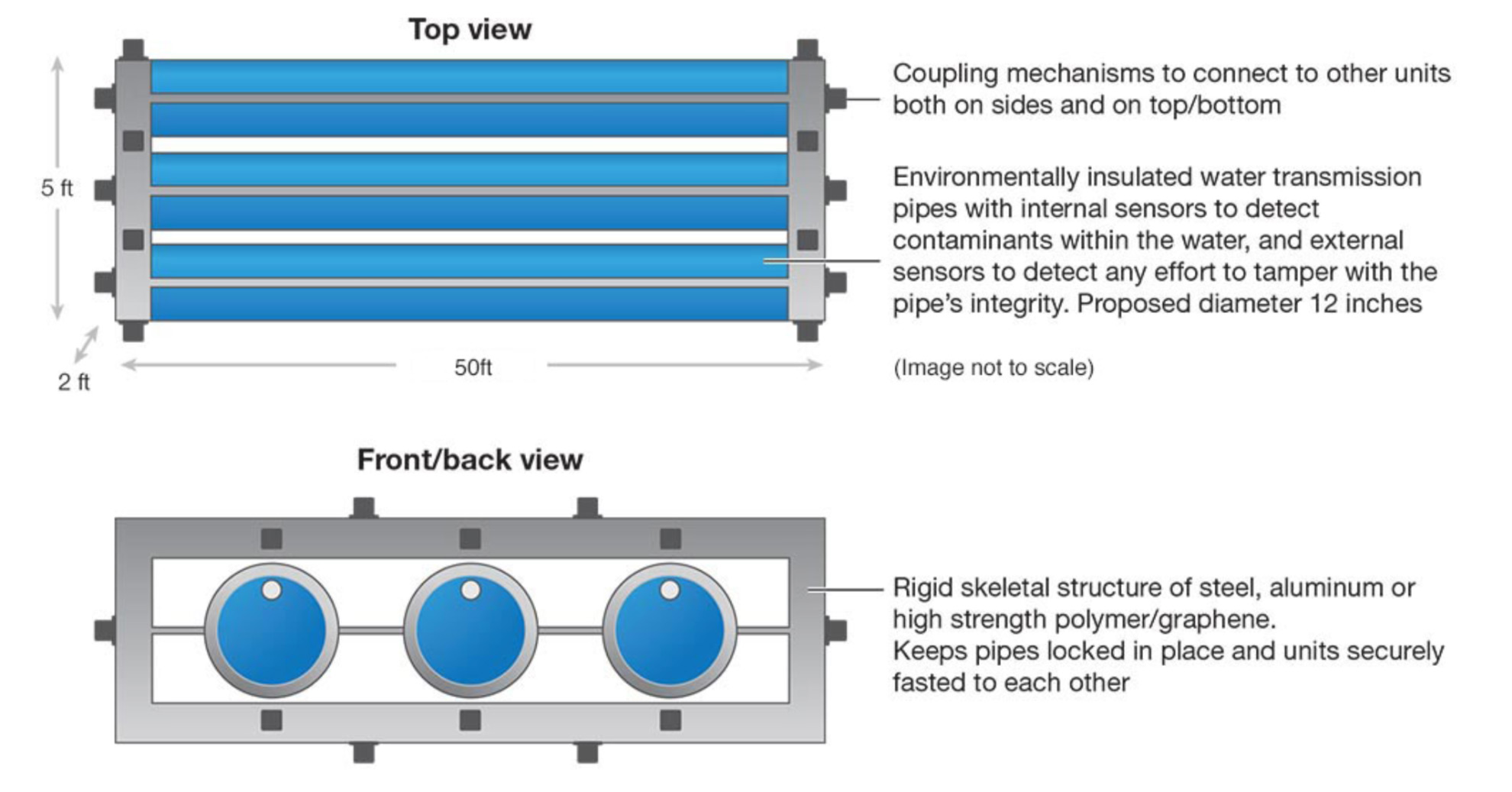

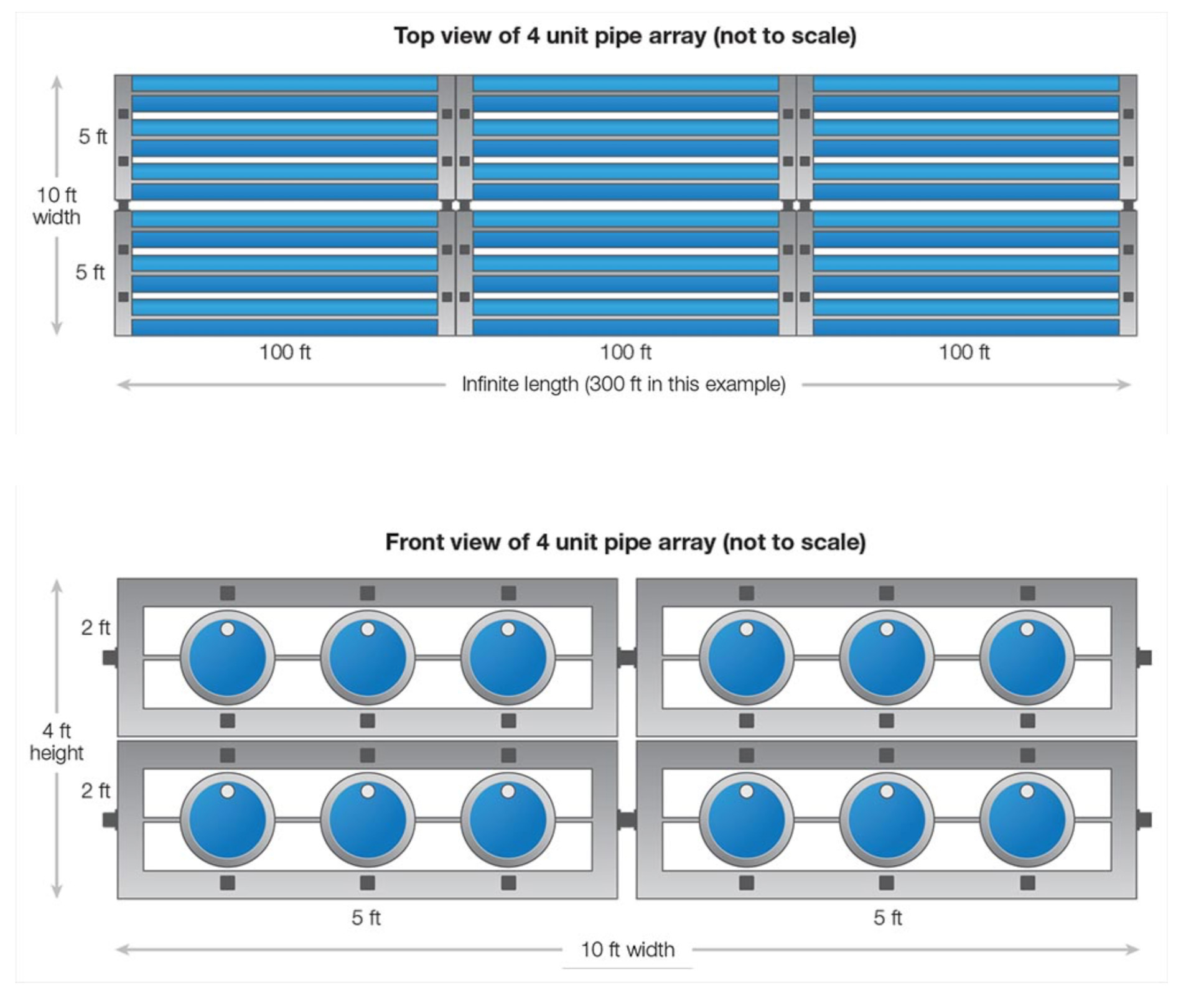

The transmission component consists of a series of water pipelines and pumping stations. Instead of building single water pipes as unique entities, the National Aqueduct would instead use factory-prefabricated pipe assemblies that are built to one standard and are designed to couple together modularly. The mindset behind this approach is two-fold: first, it would simplify construction of pipelines over long distances, and second, it provides the ability to rapidly expand transmission capacity with minimal overhead and construction costs, should the need arise.

The pipes themselves would be insulated against environmental elements and could drain or block flow on demand. They could additionally contain a series of sensors that relay relevant data to the system’s control component (described shortly). As mentioned, these pipelines would also feature external solar panels and internal turbines, which we’ll describe in detail next chapter.

The sensors within the pipeline could serve multiple purposes: they might detect contaminants, determine water quality, or send alerts if they were compromised or modified without authorization. Since each separate pipe within each pipeline could have its own sensors that connect independently to a control network, water quality could be monitored and analyzed instantly on both local and national levels.

As sensor technology has reached levels of sophistication where sensitivity in parts per billion (PPB) is common, the returned data would be useful for water management. This, among other conclusions from sensor data, could influence a range of actions from the control center of this system, ensuring maximum performance, reliability, and security.

Storage

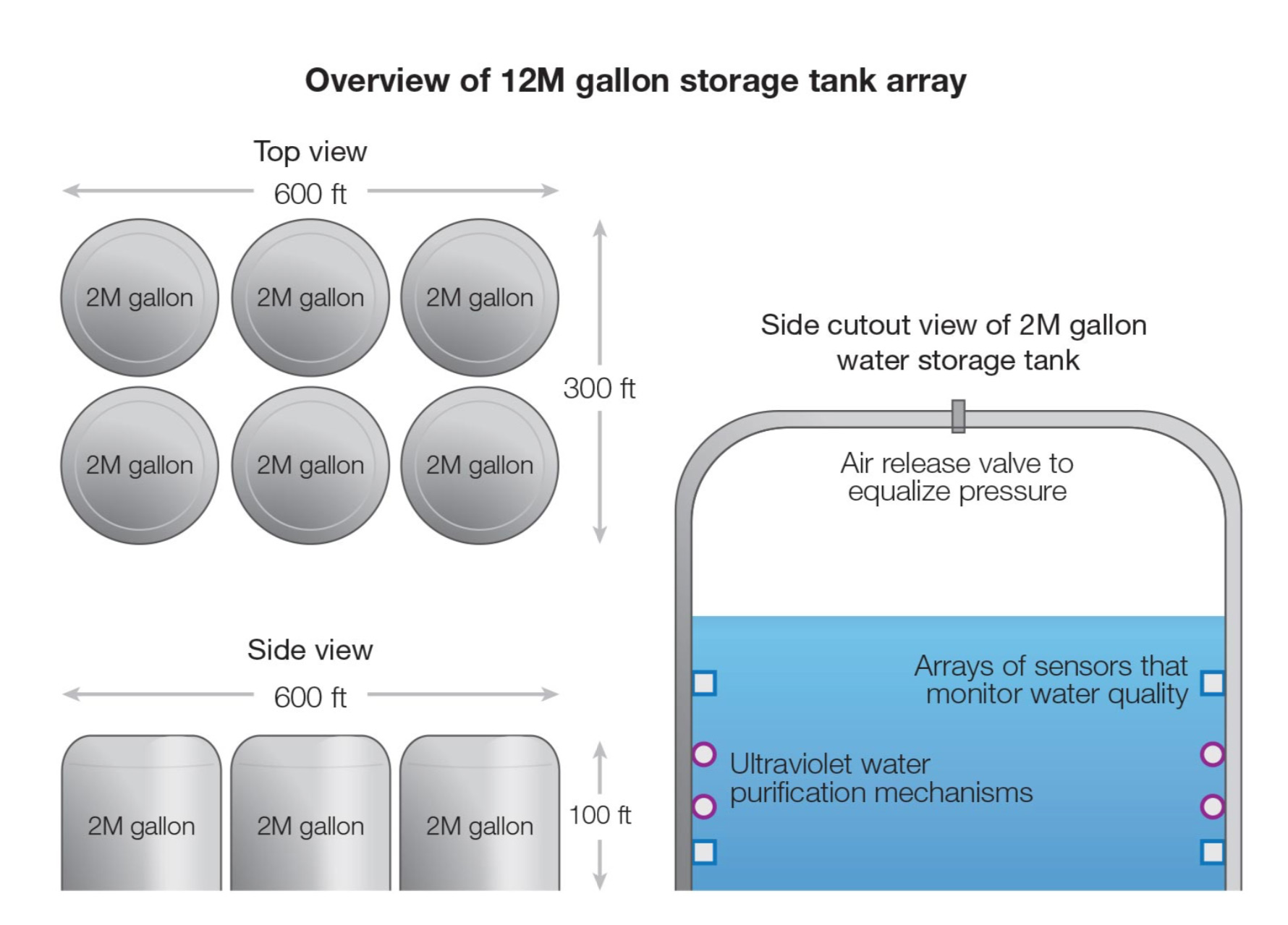

The storage component of the National Aqueduct includes arrays of containment tanks that act as the supply reservoir for a region. Rather than transport water directly from production to areas of consumption (as we largely do with electricity) this system would instead use storage tanks as a staging system. Water from the storage tanks would go directly to cities or other areas of need, and the tanks would be replenished from production facilities as necessary.

These arrays of storage tanks would contain millions of gallons of water and could be installed as distribution centers throughout the country. Each agricultural and population center would be served redundantly, with each storage center servicing multiple regions. The storage component would additionally provide several important functions:

Staging: it’s difficult to guess how much water a region might use with certainty, as external factors such as weather, time of year, and state of economy all impact how much water is consumed. Maintaining supply and pressure over thousands of miles under inconsistent demand would be a logistical nightmare, which rules out any system that delivers water directly.

However, when used as a part of a staging system water storage tanks can contain enough water to supply a region for a certain time period – say a week – which equips them to handle unexpected spikes in demand. In turn, water would be supplied from production facilities to maintain consistent levels.

This pays homage to the concept of constant resupply, which bears special mention in this context. The National Aqueduct would be constantly producing and pumping water. This consistent operation is key to meeting our immense water requirements.

For example: a common bathtub faucet has a flow rate of roughly 120 gallons/hour.[1] If that faucet was to never turn off, it would provide 2,880 gallons a day, 86,400 gallons a month and 1.036 million gallons a year – just from your bathtub faucet.

With a water velocity of just 15 miles an hour, a 12” pipe can have a flow rate of 150 gallons per second. That translates to 540,000 gallons an hour, 12.96 million gallons a day, 363 million gallons a month and 3.35 billion gallons a year. And that’s just from one 12” pipe. Imagine what an array of nine pipes could do, and imagine that pipeline array multiplied by hundreds. A constantly running pipeline network could easily transport hundreds of billions of gallons.

Overflow / active water management. Nodding to the fact that water demand is inconsistent in most areas of the country, there will be times where one region has more water than it needs or needs more water than it has. This requires the system to feature an overflow component.

By design, water storage tanks would only be filled to 70-80% of capacity, which would give them the ability to accept more water from other regions if supply exceeds demand. On the other hand, should a region consume more water than anticipated, overflow in one region can be diverted to another as necessary. With this attention to storage and re-routing, the National Aqueduct can maintain consistent uptime and high degrees of reliability.

Ultraviolet sterilization and filtration. Storing water for weeks on end can lead to circumstances where microbial agents could conceivably cause contamination. Further, there is always the concern of invasive species through any sort of aquatic transfer (think Zebra mussels).[2] In addition to standard filtration mechanisms and high temperature of water, the Aqueduct’s storage and transmission component would have a series of UV lights to further sterilize stored water. Ultraviolet light, especially at high intensity, is lethal to any microbial lifeform (bacterial or viral) with high reliability, allowing for long-term water storage without fears of stagnation or outside contamination.

Control

The control component is the brain and central nervous system of the National Aqueduct, yet also works as a decentralized framework allowing any region to control the flow of water in its jurisdiction. This would be accomplished through a series of manned control centers at national, regional, state and local levels, similar to the current management functions of large public utilities.

In this case, the control component would monitor the system to ensure consistency and stability, and further act if it detected a contaminant, outside tampering, or mechanical failure.

In the event of a shortage or an overabundance of water in an area, water could be routed from one storage array to another as necessary; in the event of a problem, the control component could direct the “smart grid” of transmission pipelines and pumping stations to take action. These actions might range from disabling, draining, and isolating a certain section of pipes from transmission lines, to bypassing a whole sector or storage array completely.

The sensor network within the National Aqueduct could further provide data to create models that would be greatly beneficial toward ideal operation, and which could, for example, predict demand over time. A defining feature of the National Aqueduct is that once enough water has been produced, the production component only needs to resupply what has been consumed, allowing desalination facilities to produce fresh water only as needed. Accurate modeling allows water to be resupplied intelligently – knowing when water will be used at what levels based on time of year allows us to address anticipated shortages before they occur.

The National Aqueduct is Scarcity Zero’s means to deliver water anywhere in the country, allowing us to live free of the destructive results of unsustainable water use and natural drought cycles. From here, the secondary component of the National Aqueduct comes into play – in addition to supplying the nation with water, it can store electricity generated by renewables on a massive scale, making it the “world’s largest battery.” Next chapter, we’ll explore why.